In the world of professional audio engineering, few projects stand out as both exhilarating and daunting as recording a live performance with a legendary band like Weezer. For Jack Mason, a seasoned recording engineer at Spotify, this opportunity was a dream come true.

With a career that began with a humble recording setup in high school, Jack’s journey has been marked by a relentless pursuit of excellence, eventually leading him to work with some of the biggest names in the industry.

In this interview, Jack shares his experience recording Weezer live in the studio for Spotify’s Anniversary video series, offering insights into the meticulous process, the challenges faced, and the role AEA ribbon microphones played in capturing the magic of the session.

Can you tell us about your background and your career as an audio engineer?

I fell in love with recording during my senior year of high school. It all started with a very early edition of GarageBand on an old MacBook, and eventually, I upgraded to Cubase. I played in pop-punk bands throughout high school and college, where we made a few EPs. While I studied music at the College of the Holy Cross, I always knew that recording and producing music was my true passion.

A turning point in my career came when a family friend, Jeff Jones, a phenomenal engineer in NYC, called me one day. He told me about a job opening at a great studio in Manhattan and encouraged me to interview. Despite having no formal studio experience or a degree from a more expected institution like Berklee, I went for it. I was a blank slate, and I think they liked that I could be molded into a textbook assistant. I landed a job as a runner (also known as a general assistant or “tea boy”) at MSR Studios in NYC.

MSR was one of the last true large-format recording studios, with multiple rooms, including two with 72-channel SSL 9000J consoles and a B room with the Euphonix System 5 (now Avid S6). My experience there was very old-school, working my way up through a traditional studio hierarchy. For three years, I climbed the ranks, including a brief four-month apprenticeship in the tech shop under the chief engineer, Brad Leigh—a brilliant engineer. I learned more during those months than I can begin to unpack. Brad is still someone I consider a go-to “phone a friend” for anything session or tech-related, and we still collaborate to this day.

As an assistant engineer, I worked with a wide range of engineers on various sessions, from overnight hip-hop sessions to full days of Broadway cast albums. The exposure taught me different techniques, protocols, and crucially, how to manage personalities—mostly through observation. It was a massive exercise in patience, something I had to learn the hard way since patience doesn’t come naturally to me. My “big break” came when I worked on J. Cole’s “2014 Forest Hills Drive.” I spent almost four months on that project, effectively living at the studio. By the end, I was tracking vocals in one room while Mez was mixing in another. I recorded horn sections, some strings, and the final track on the album, which was mostly recorded live off the floor. That experience remains on a pedestal for me—I wish I could make every album that way.

Eventually, I faced the proverbial choice: go freelance or stay at the studio. Unfortunately, the choice was made for me when the studio shut down and relocated in August 2016. I freelanced for a few months, though not particularly successfully, and then I saw a job posting for an assistant engineer at Spotify on Indeed.com. The rest, as they say, is history.

How long have you been working at Spotify, and what are some of your favorite things about the gig?

I’ve been with Spotify since January 2017, so it’s been a little over seven and a half years. I started as an assistant engineer in NYC, eventually becoming the recording engineer for the in-house studio run by Bryan Grone and producer/mixer William Garrett. I relocated to LA in 2020 under Chris D’Angelo’s studio facilities team to help finalize the build-out of our LA studio, and I now work across multiple programs on our Music Studios team as the producer, mixer, and engineer under Sarah Patellos.

There are too many things I love about the gig to list them all, but a few highlights stand out. First, the balance it’s brought to my life is incredible. I’m fortunate to make music with amazing artists on programs that genuinely serve the artist community. The artists own all of the music masters we produce at our studios. I work weekdays during regular hours, which means I’m usually home by 6:30 most nights and get to put my one-and-a-half-year-old twins to bed every night.

Another thing I love is the sheer number of artists I’ve had the privilege of working with—probably somewhere over 300 at this point. It’s been a very classic studio journey but in an entirely unique music industry landscape. And of course, the studios I’ve been blessed to work in are just beyond anything I could’ve imagined. From our first room at 18th Street to Electric Lady and eventually to Spotify at Mateo, a WSDG studio I had a hand in designing from the ground up. It’s a dream come true—sometimes I still can’t believe it’s real.

What was it like working with Weezer? Were you a fan of their music?

A friend handed me the Blue Album CD in the back of his family’s Suburban while we were on vacation as kids. I remember hearing it on my Discman for the first time and thinking, “I didn’t know music could sound like this.” I was the child of two incredibly non-musical parents who mostly just listened to Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Elton John, and Queen. No complaints there, but I just wasn’t exposed to a wide variety of music as a kid. I really got into alternative rock through friends in my tween/teen years. So yes, it’s safe to say I was a fan of their music, and safe to say it was a very full-circle moment for me.

I felt a tremendous sense of pride, excitement, and fear getting to work on this project. Re-recording versions of iconic records doesn’t always play out in favor of the new recording team. I’m grateful this one has been so widely viewed and highly regarded.

Can you describe how the live session was set up for recording?

The concept of this series is a hybrid of live performances broken up with talkback sections that we refer to as group therapy sessions, unpacking the history, stories, and nostalgia that come along with making records. We knew we wanted them all in the same room, and we wanted it to feel like a garage band rehearsing, or like the band was practicing for a show in their basement—except in our case, it was the best-sounding live room in LA.

We had some chairs and stools and ottomans scattered around the band and a couch hosting some special guests, like Karl, Suzy, and Barry. Rivers ended up facing Pat (drums), which was a huge part of how we were able to keep his vocal so clean. I thoroughly edited out and muted the background vocals when they weren’t singing.

Pat tweaked our ’50s Slingerland Radio King Kit, but not much. Kick in was miked with a Beta 91, kick out was a FET 47, and a custom subkick. Snare top and bottom are always Beta 56A mics, toms are DPA 4011s, Soyuz 013s for hat and cymbals, and an AKG C24 and Coles 4038 for overheads/kit. I think I had a few room mics too—probably more Soyuz SU103s high up on a tree and an AEA R88 mk2 a bit lower.

Bass was interesting because we had a DI where the thru output fed a pedal board, and then that pedal board fed two amps—an Ampeg B15 for the general “clean” tone, and then a Fender Deluxe Reverb that we used as a dirty channel that Scott kicked on occasionally. I’d never used a Deluxe Reverb for bass—it was pretty sick.

Brian played through a DI that fed his pedalboard which then split out to our Marshall 50w Lead for this dirty channel and our Vox AC30 for his clean channel. Rivers used his kemper and we also fed a post-amp sim feed into our Magnatone 260. It was an odd combination that just worked. I wanted an even amount of each player pumping out into the room so my room mics could be balanced across the band.

Every channel went through the Neve Shelford console. I don’t remember exactly, but I probably EQ’d everything because the Shelford EQs are incredible and I like them for broad strokes, although I do go pretty extreme with them on drums.

For compression, I left the guitars untouched; the bass went through LA2As. Kick in and out through dbx160As, Snare top and bottom through Distressors, room mics through my Obsidian, and the unFairchild on the overheads, maybe doing a dB of limiting on big snare hits. I didn’t compress the vocals on the way in, which is uncharacteristic for me, but not knowing the mics very well combined with being in the room with drums, I just wanted to play it safe and make sure we didn’t get any pumping artifacts from the cymbals.

We did one take of each song—no comps, no overdubs.

What did you want to capture during the recording—and how did you want the mix to sound?

I always record DIs in the instance I need to re-amp something. In this case, I didn’t need or want to. They’ve been playing these songs for 30 years. They’re all very particular about their tones, and I respected committing to that sound. I just wanted to capture the energy of the band playing in a room together with no frills, no overdubs, and no playback tracks. Just the band in a room.

When I mix rock bands like Weezer I tend to over-polish, and then the band or artist pulls me back to more rawness and reality. I’m often guilty of not leaving in the peels and rinds, and it’s something I acknowledge upfront and always try to keep myself in check. I don’t want the record to live in a vacuum of perfection.

I worked closely with their manager Dustin Addis to get the right balance of grit and polish. We needed to pay homage to the original album, but in no way did I want to emulate or recreate it. I wanted this to be fresh and a new sonic experience for listeners and fans. I did however honor a staple of the original record-making process, which was no added reverb. I also accepted the fact that technology in 2024 allows us to do things like use lalal.ai to remove bleed from mics.

Combine that with the mic choices and recording techniques and it was the first time I was able to mix a live record like a studio record. Those are the primary reasons these recordings sound so pure (and why some listeners have claimed we did overdubs, which was not the case). Not to mention the source material was just great to begin with.

I don’t really believe in dogma in audio. But, less clutter and fewer instruments means each individual instrument has its own bandwidth to breathe in the mix. That translates to bigger sounds and more headroom. For the gear heads out there, I mixed this with a hybrid workflow — Pro Tools was the multitrack recorder and mix engine. I used a plethora of plugins, and the multitrack summed down to instrument group busses which fed faders on the Neve 5088 Shelford Console. The Shelford console mix output fed back into Pro Tools via the RND MBC and then fed a mix buss with some more plugins and outboard gear as hardware inserts (Neve 33609, and UTA unFairchild). I use a top-down approach to mixing. All of the routing and plugin/hardware usage is on from the start of the mix process.

Did you use any other AEA mics during the recording?

I used three AEA N22s, one on each guitar amp (Marshall Lead, Vox AC30, and Magnatone 260), and a R92 on the bass amp (Ampeg B15). The reduced proximity effect on the N22s was essential because I wanted those right up on the speakers. They are bidirectional after all, so I did use the sE GuitaRFs to help with additional isolation and blocking room reflections into the back side of the mics. I was worried the AEA R92 was going to be too bass-heavy on the B15 but we found the right balance of EQ on the amp itself to help offset the proximity effect, so it just slid into the mix and with a shockingly low amount of bleed from the adjacent drums.

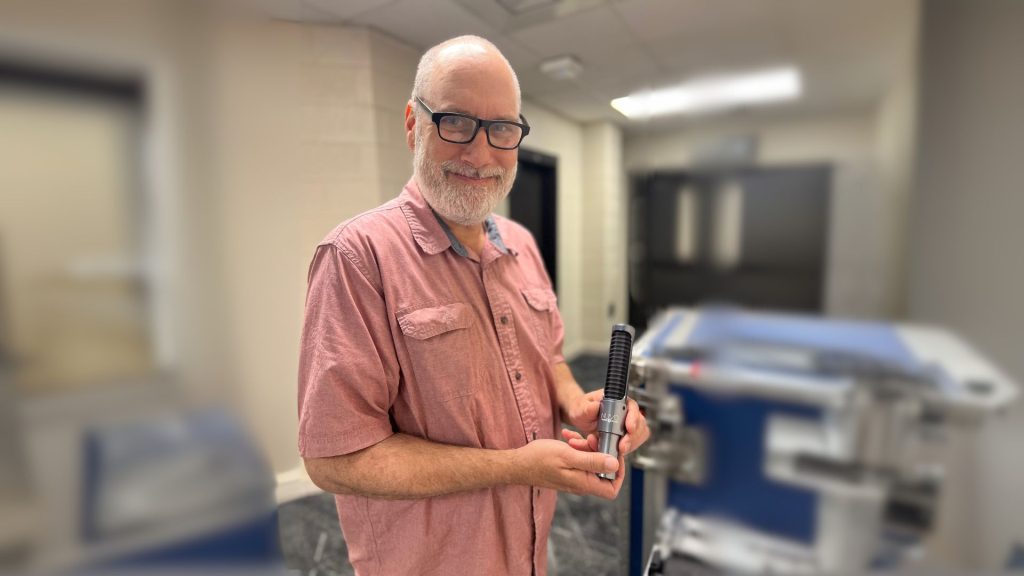

What feature were you looking for, or what problems were you looking to solve by using the KU5A?

I needed clarity and isolation in a room filled with amps and drums. I had Pat on Drums, Scott’s Bass through a clean amp and a second dirty amp, then Brian’s clean amp and dirty amp, and River’s guitar coming through the Magnatone, plus three vocal mics — all in the same room. I was going to do anything and everything I could to minimize bleed into those mics, especially since the director and producer wanted a gobo-less setup. The KU5A’s are a huge part of why the recording sounds so clear.

How did you first hear about AEA and the KU5A, and why did you choose it for vocals?

My engineer friends Suzy Shinn and Alex Venguer are always posting about AEA mics. Suzy and I used the AEA R88 all over the Sad Alex Spotify Singles we worked on, as well as some of Suzy’s solo stuff we recorded. I’ve had an R88 for years and I got a couple of the AEA R44s when I wanted some more ribbons but didn’t want to go through the hassle of finding vintage ones in good condition. With AEA, I just know they’ll work. Alex Venguer was posting about how much he likes the AEA KU5A when he’s recording multiple vocalists in a room and I thought: “Hey, AEA are just up the street from me in Pasadena, I wonder if they’d lend me some mics for this Weezer shoot?”

The more I think about it, the crazier I feel for trying new gear I hadn’t ever heard on my first recording with such an iconic band. But I’m glad I did. The rejection is amazing and they are incredibly full-bodied without being woofy with a very smooth top end, which is rather shocking for super cardioid mics (which I usually expect to be a bit more focused and pinched sounding). I still don’t understand how the ribbon—which is traditionally bi-directional—is super-cardioid. But in this case, it rules.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

I think this may very well be my first solo interview. So, I’m incredibly grateful to AEA for not only being a huge part of the sound of this show, but for the opportunity to share a bit about myself and my experience working on a project I’ll treasure forever. Hit me up if you want to talk audio or twins or pizza—or if you’re in LA and want to be best friends.

Get in Touch with Jack:

Instagram: @auxillaryjack

Linktree: https://linktr.ee/auxillaryjack